Types of Measurement Error

Self-report dietary assessment instruments are affected by two main types of error - systematic and random ([glossary term:] within-person random error) - that must be understood and addressed in order to avoid misleading results.

Systematic error

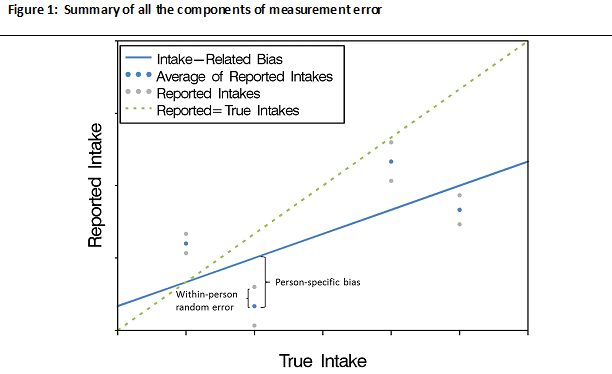

[glossary term:] Systematic error (also known as [glossary term:] bias) is a type of error that results in measurements that consistently depart from the true value in the same direction (Figure 1). In contrast to random error, data affected by systematic error are biased, and this type of error cannot be reduced or eliminated by taking repeat measures.

The main elements of systematic error include:

- Intake-related bias: The part of systematic error that is related to, or a function of, true usual intake. An example of this is the "flattened-slope" phenomenon by which people with higher true intake tend to under-report and people with lower [glossary term:] true intake tend to over-report.

- Person-specific bias: the difference between total systematic error and intake-related bias. It may be related to individual characteristics, such as social/cultural desirability, that affects how a particular individual reports dietary intakes.

Within-person random error

Within-person random error (also known as day-to-day and within-person variation) is the difference between an individual's reported intake on a specific administration of the dietary assessment instrument and an individual's long-term average reported intake based on many multiple administrations of the same instrument. Data affected by within-person random error only (i.e., no systematic error) are not biased but may be imprecise.

What we eat and drink tends to change from day to day. However, in estimations of usual intake, [glossary term:] day-to-day variation is considered to be a source of within-person random error, even if an individual accurately reports his or her intake for a given day (e.g., using a 24HR or food record). In addition to day-to-day variation, there may be other sources of within-person random variability, such as error in measurement on a given day, that affect reported intake data.

Figure 1 summarizes all the components of measurement error by illustrating the two types of systematic bias (intake-related and person-specific) and within-person random error.

Taking Measurement Error into Account when Estimating Usual Dietary Intakes

If [glossary term:] within-person random error is the only type of error in the data and if repeat measures have been taken, averaging across days will provide a better approximation of [glossary term:] usual dietary intakes than will a single day's measure (Learn More about Usual Dietary Intake). In reality, however, investigators usually do not have sufficient resources to take repeat measures often enough to obtain an accurate assessment of usual intake for each person in the sample [1]. However, given at least two measures on at least a portion of a sample, statistical modeling can be used to adjust for the effects of [glossary term:] day-to-day variation to arrive at estimates of usual intake for the population or subpopulation (see Effects of Measurement Error).

In contrast, it is not possible to correct for [glossary term:] systematic error using averaging or statistical modeling. As a result, a [glossary term:] reference instrument (i.e., a measure assumed to provide unbiased estimates of [glossary term:] true intake, such as a [glossary term:] recovery biomarker) is required. This is a challenge for dietary intake data because reference recovery biomarker instruments are known for only a few dietary components, and unbiased reference data obtained from observation or feeding studies are generally impractical or infeasible for most studies. As a result, from the perspective of minimizing measurement error, it is preferable to use an instrument that minimizes systematic error and to take steps to address within-person random error.